1. INTRODUCTION

Motivation is one of the most prominent individual difference variables (Dörnyei, 2006), and as such a significant predictor of behavior and academic achievement (Abouserie, 1995; Pintrich, 1999; Wigfield and Eccles, 2000) including learning another language (Dörnyei, 1994; 2001; Noels et al., 2000; Skehan, 1991). Language teachers are intuitively familiar with such belief inasmuch as they use the “motivated” and “successful” adjectives synonymously for good language learners since for learning a second language (L2), which is a lengthy and mostly tedious process, “the learner’s enthusiasm, commitment and persistence are key determinants of success or failure” (Dörnyei, 2010. p. 74).

Since the birth of the L2 motivation field in 1959 by Robert Gardner and Wallace Lambert, there have been numerous validations and studies of the role of motivation in L2 learning. Moreover, the field has witnessed a number of stages characterized by different theoretical models and in response to both needs of the field and developments in the wider educational psychology (for a review see Al-Hoorie, 2017). While classical approaches had tackled the issue in the form of investigating possible motives, the newest conceptualization sees motivation as a complex, dynamic process, difficult to predict and hard to study in isolation (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013). In light of this latest trend, limiting motivation research into static and universal motives is incomplete regardless of how expanded the list of motives might be or the level of scrutiny the research goes under. Nonetheless, with the lack of predictability, researching motivation as a dynamic system is almost impossible. As such, investigating motivation in the form of motivational phenomena might be a better way to understand the possible parameters of motivational intensity while acknowledging the complexity of motivation. Furthermore, studying motivational phenomena ensures that the temporal and contextual aspects of motivation are taken into account (Dörnyei and Ottó, 1998). Directed motivational current (DMC) is the latest concept in the field which represents a motivational phenomenon characterized by intensity and sustainability.

The term “DMC” refers to a motivational experience in which one is engaged in intense activities triggered by and in pursuit of a personally meaningful and valuable goal for which a salient, facilitative pathway is utilized. A DMC can also be described as “an intense motivational drive which is capable of stimulating and supporting long-term behaviour,such as learning a foreign/second language” (Dörnyei et al., 2014. p. 9) and “a prolonged process of engagement in a series of tasks which are rewarding primarily because they transport the individual toward a highly valued end” (Dörnyei et al., 2015. p. 98).

The notion of DMC first originated from the personal experiences of the three authors behind the theory, Dörnyei et al., who had also identified similar observations in other people around them. They then coined the term that, to them, best described the novel phenomenon; “directed” signifies the first component of DMCs, namely, that engagement is always directed toward a specific goal; “motivational” depicts the intense motivational feature of the experience; and “current” is a metaphor suggesting the similarities that exist between the sustained phenomenon and a strong current, such as the Gulf Stream (Dörnyei et al., 2014).

DMCs are believed to be a specific period of time distinguished from other periods by extraordinary motivational intensity. Individuals experiencing a DMC and often people around them are usually aware of the uniqueness of their experiences. Dörnyei et al. postulate that a DMC occurs when a number of personal and contextual factors come together to create a powerful surge of motivational force, known as the DMC launch.

A DMC’s launch is also similar to an oceanic current’s geographical starting point which “transports the various marine life-forms caught up in its flow along its predefined pathways” (Dörnyei et al., 2016. p. 58). That is, the launch can determine not only the intensity of the DMC experience but also and more importantly, the subsequent pathway for the entire DMC behavior. For that reason, “the successful launch of a DMC arguably constitutes half the battle in the experience of such motivational currents” (p. 58). A powerful and elaborate DMC launch is central not only to setting up the initial motivational surge but also more importantly to the continuation in the subsequent stages of the process, a mechanism which Dörnyei et al. (2014) dubbed “motivational autopilot,” through which “the initial momentum rules out the necessity for a motivational intervention each and every time a new step within the sequence is to be carried out” (p. 14). Hence, understanding the initial conditions including the launch of a DMC is vital for understanding not only how a DMC might come to being but also how educators might engineer DMC or DMC-like experiences in second language learners. This study is, therefore, aimed at addressing these two areas of DMCs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The main research question of this empirical investigation was: What are the parameters that lead to the occurrence of DMC? To answer this question, this study collected data about the initial conditions before the emergence of the subjects’ motivational surges. As DMCs are not expected to appear suddenly or drift into being, understanding the general initial circumstances around the time of a DMC launch is necessary to learn about the possible parameters that lead to contribute to a DMC journey.

2.1. Data Collection

The recruitment aimed at capturing cases of DMCs among individuals who had experienced at least one DMC while engaged in learning a second language. Yet, the challenge, as is the case with investigating a new phenomenon, was to identify DMC cases in participants who would not have knowledge of the concept. The initial stages of data collection started with distributing a call for participation flyer among colleagues and social media outlets. The flyer wondered if one has experienced a period of intense motivation while engaged in L2 learning. This process was conducted in the UK and Iraqi Kurdistan as part of a larger empirical project on the DMCs (Ibrahim, 2016b).

On receiving responses about the occurrence of such intense periods of engagement, over 35 participants came forward. A thorough screening procedure was carried out to determine whether the cases collected were indeed DMC, DMC-like, or simply regular motivational experiences. The criteria used to do so were based on the theoretical foundations outlined by Dörnyei et al. (2014; 2015): (a) Experiences stand out by motivational intensity beyond normal, everyday motivational levels, (b) goal-orientedness, (c) positive emotionality, and (d) the use of a unique and distinguishable structure for learning.

As such, out of 17 DMC cases, structured and semi-structured interviews were conducted to gain more information about the cases. A number of participants provided their answers electronically in the form of written accounts. The interviews and written accounts were in either English or Kurdish. A number of further cases were left out due to insufficient data about the experiences or when contact for further rounds of interviews was not possible. In the current study, 9 cases of DMCs are presented about which sufficient data were available about the initial conditions of the experiences to conduct a meaningful process of analysis.

2.2. Data Analysis

All the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The interviews conducted and the written accounts obtained in Kurdish were then translated into English by the researcher paying special attention to the accuracy of the English versions against the original recordings and texts. Although a holistic approach was used in the analysis of the entire dataset, the current study presents only the results of the analysis of the initial conditions of the participants’ DMC experiences.

A phenomenological approach was used for the analysis of the data to capture the “universal essence” and meaning of the phenomenon in question as lived and experienced by the participants (Creswell, 2007. p. 58). This method was believed to be particularly useful in investigating a new phenomenon such as DMCs to gain a thorough understanding of what the participants experienced and how and why they experienced them (Moustakas, 1994). A modified (a combination of descriptive and hermeneutic interpretive) approach as described by Colaizzi (1978) and Moustakas (1994) was used as below:

-

The dataset was all merged together and read several times to obtain a general feel for it. Manual coding was used at this stage leading to an initial codes manual.

-

Afterward, the researcher went through the entire dataset and extracted a non-overlapping list of the significant phrases and statements, treating them as of equal worth. The criteria used for selecting these statements were: A statement needed to be around a DMC experience (e.g., not giving a general opinion on how to best learn an L2); and it had to provide a new - not repeated - piece of information. However, all the similar codes with variations, slight or prominent, were fully considered.

-

Formulated meanings, that is, interpretive meanings, were produced for each statement.

-

Clusters of themes (Colaizzi, 1978) were developed from the combination of similar formulated meanings. In developing a cluster of themes, the researcher made efforts to “stay as true to the phenomenon as possible” and to “bracket” his presuppositions about the phenomenon (Hycner, 1985. p. 287).

-

Independent themes were produced from similar theme clusters (Sanders, 2003). All the initial manual codes developed earlier were categorized under each theme to measure their frequency and account for variations.

-

In parallel to this process of developing the raw data into common patterns and themes, a descriptive account was produced for each participant’s narrative reflecting “what” happened (i.e., textual description) and “how” the experience happened (i.e., structural description). Both of these descriptions were combined in a single composite description reflecting the “essence” of the experience (Creswell, 2007. p. 159).

The entire data analysis was bottom-up, and iterative process and analysis were initiated at the early stages of data collection. In the analysis, the theme clusters and themes were worked through and re-examined numerous times to achieve scrutiny and scientific rigor (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2008; Finlay, 2012). Therefore, close attention was paid to ensure that the final themes represent what was dominant in the data, so the final presentation describes the bulk of the data rather than deliberately selecting extracts to support specific claims (Joffe, 2012).

3. RESULTS

The phenomenological analysis generated three themes in relation to the initial circumstances around the DMC experiences. As a result of utilizing an inductive approach to analysis, these themes are thought to represent the most significant aspects of the dataset in regard to what contributed to the launch of the participants’ DMCs and the possible conditions. In presenting the findings, emphasis (underlining) has been added by the researcher, and quotations of the participants (which are reproduced verbatim and essentially uncorrected) are numbered (e.g., Suzan, Q1) for ease of cross referencing.

3.1. Theme 1: Clear Starting Point

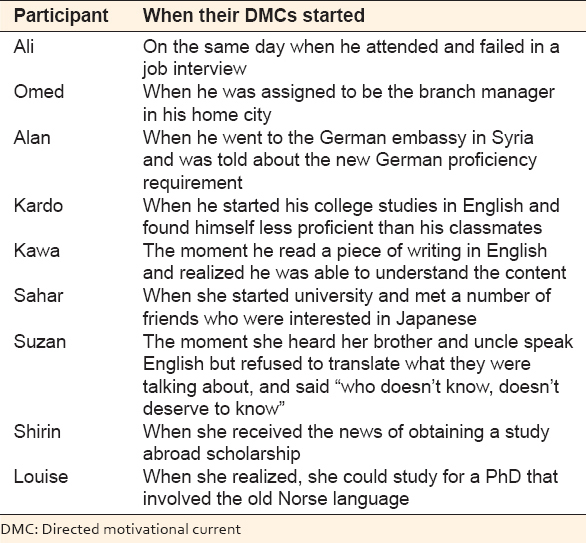

All the nine participants clearly remembered when their intense motivational experiences started. They were asked the question (What made your experience start?), and all of them provided an answer not only about the time but also the detailed circumstances before, and around the time, their experiences started. The starting points were described in relation to specific events or occasions. Table 1 summarize the exact occasions marking each of the participants’ starting points.

Table 1: Participants’ DMC starting points

3.2. Theme 2: The DMC Trigger

As well as a clear starting point, all the participants discussed a specific event in reference to what made their experience start. None of the participants’ experiences were drifted into being from a sudden decision but were - or perceived by the participants to be - caused by a particular incident or as a consequence of a specific triggering stimulus. These triggers were one or more of the following.

3.2.1. Emergent opportunity

Four participants referred to a newly arising opportunity which played the main role in setting up their DMC experiences. Shortly after graduation from university, Omed, for example, was appointed as a new branch manager for which he needed to develop his communication skills in the L2. To him, this was a valuable opportunity after he had secured and successfully completed a competitive internship. Shirin’s DMC was triggered when she became aware and obtained a fully-funded scholarship to an English speaking country. To her, this was a sudden and hard to believe opportunity so she could improve her English skills because she had held the belief that she was unable to achieve this dream in her own country:

Learning and improving English was my biggest objective, even more important that obtaining the MSc… It was a dream come true, because earlier I would see studying in the UK as almost impossible due to difficulty in obtaining a visa, high tuition fees, travelling and other factors. However, this opportunity suddenly became available. (Shirin, Q 1)

3.2.2. Negative emotion

Two of the DMC cases were triggered by negative emotionality stemming from a failure or a negative statement. Ali’s DMC was triggered immediately after he attended a job interview in which he was unable to answer the questions in English. As a result, Ali came out from the interview “shocked” and humiliated, feelings that made him realize his poor L2 skills and the need for improvement and positive change, as he recalls:

Ali: … After hello, they started speaking in English, which I never thought would be the case. I was getting dizzy as they were speaking. I used my broken English and said a few words like, ‘wait, I am not good’, I can do it in Kurdish only… They looked at each other, apparently saying it was not possible, and I got it.

Interviewer: So the interview ended?

Ali: It ended right there… I still remember this very well, and think it happened yesterday. I came out from the building, shocked, and couldn’t even focus on what the person at the reception, whom I knew, said to me. I was in a weird situation…. (Ali, Q 1)

The effect of this event was dramatic. He further recalls his reactions and thoughts immediately after the failed interview and while in his car going home:

The impact was huge… When I put my hands on the steering wheel, I said to myself, “Ali, you have to move just like this car”, and “you can’t stop where you are”… This is different than before; I was not really into English before and I didn’t care much about it. So this was my turning point. (Ali, Q 2)

As can be concluded, Ali was most affected by his affective reactions to his inability to use the L2 and what interviewers told him rather than the event itself. In that respect, the failed interview served as an opportunity for him to reflect and realize his inadequacy.

Suzan’s experience was also triggered by a negative emotional reaction to a statement by her brother and uncle. Although she was younger in age (a teenager at the time), she found their statement about her L2 understanding skills to be humiliating and demeaning, which aroused a sense of anger:

We were a family group, where my uncles and my brother speak in English so no one can understand them. I asked them to translate, and they said “the one who doesn’t understand, he doesn’t deserve to know what we are talking about”… I became very angry and I had to do something about it. (Suzan, Q 1)

3.2.3. Moments of realization/awakening

In addition to experiencing negative emotionality, both Ali and Suzan also experienced a sense of realization and awakening. They both discussed their feelings after the events and also the statements made about their inadequacy. In turn, they thought about and considered the directions they needed to take and the consequences of not taking action. When Ali was unable to proceed with the job interview in English, he was asked to leave, and despite the feeling of failure, the event made him contemplate why this happened and what went wrong:

I remember it very well, he [Ahmed, one of the interviewers] put his hand over my shoulder, and said to me, “I know you, and that you have good experience and skills. Improve your English to have more opportunities”… I went into my car and waited, thinking of Ahmed’s speech… Ali, you can’t go any further if you don’t improve your English. I realised I would remain in the same circle without English…. (Ali, Q 3)

A similar trigger was identified with Kardo when he realized he was less proficient in English than his classmates on being admitted to a university that instructed in English:

I got accepted anyway [to the university]. I was feeling very shy and nervous during my class times. I saw most of the students speaking in English, I figured out, later, is very weak English, but for me it was native English. (Kardo, Q 1)

Kardo felt insecure in his new environment mainly due to the perception that his classmates were proficient English speakers. Given that this event occurred in the early days of his 4-year-long university life, Kardo felt a sense of awakening about his L2 status and a strong need for improving his English. Later, Kardo discussed how he mainly focused on developing his speaking abilities, among other skills, as his intense experience was triggered by becoming conscious of his lack of communication skills in the L2.

3.2.4. New information

One participant’s DMC was in large part triggered by receiving a piece of information which made him enroll in an L2 learning course. On his marriage to his German wife who was visiting Kurdistan where Alan was from, Alan later went to Syria to apply for a visa to join his wife. He was, however, advised of a new regulation “that required sponsorship applicants to know German before granting them a visa.” Although unexpected and even “shocking,” it did not take long for Alan to make a resolution to stay in Syria and study toward a German A-Level certificate required for the visa.

3.2.5. Meeting friends who shared passion

Although Sahar had long had an interest in learning Japanese so she could understand Japanese anime as she was not satisfied with the dubbed versions, her intense learning experience was only triggered when she entered the university and met a few friends who shared a similar passion for Japanese culture and movies:

So I met a few people who were really interested in Japanese animation and movies, drama and everything that was to do with Japan. So because of my friends, then I was kind of drawn into it as well. And we started making our own group. We took on Japanese names; we started trying to learn the language; we watched Japanese films together, watched Japanese animations together…. (Sahar, Q 1)

As a native of Saudi Arabia where making contact with Japanese speakers was almost impossible, Sahar found the environment in which she met people with whom she used Japanese which now seemed to be a living language. The above extract also suggests that the generation of Sahar’s DMC had a social component in that Sahar and her friends formed a friendship circle centered on learning and using Japanese insofar as they adopted Japanese names and engaged in learning activities together.

3.3. Theme 3: DMC Conditions

Despite that all the DMC cases were triggered by specific events and triggering stimuli, the analysis identified a number of conditions that seemed to be necessary before the DMCs in order for the above-mentioned triggers to be effective. Below I discuss these conditions and the interplay between the DMC conditions and triggers.

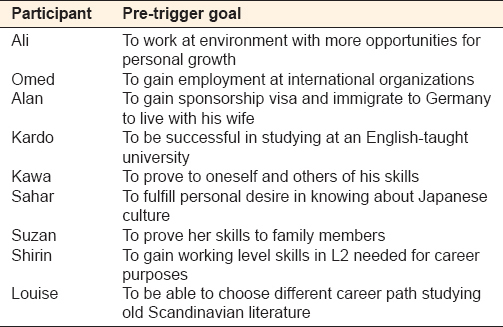

3.3.1. Goals/ambitions

Before their DMCs, all the participants had some kind of goals or future wishes they hoped to reach, related to their potential DMCs and which had important implications for making them prepared for their DMCs. Although many of them had a pre-interest in learning/improving their DMC-L2s, the pre-DMC goals were mainly ambitions for personal and developmental growth rather than learning an L2 in its own right. As such, these goals were mostly general dreams and desires for a better future state such as being successful at one’s career or being able to do something in life which one always wanted to. Table 2 summarizes the participants’ goals/ambitions before their DMCs. As seen, these goals were not in regard to acquiring a certain level of L2 proficiency for its own sake; most of the participants wished to achieve goals for which learning an L2 was perceived as necessary.

Table 2: Participants’ pre trigger goals/ambitions

All the participants had goals that not only did they consider valuable and significant but also their attainment seemed to have great influence on their personal lives. However, despite the fact that all the participants had a goal-oriented background, simply having a goal did not lead any of them to experience a DMC or a DMC-like motivational surge. That only happened once a triggering stimulus became available which set up their DMCs. Evidence backing the claim that goals did not lead to motivated behavior is apparent from all the DMC cases in which the participants had had the general goals for a relatively long period before their DMCs started.

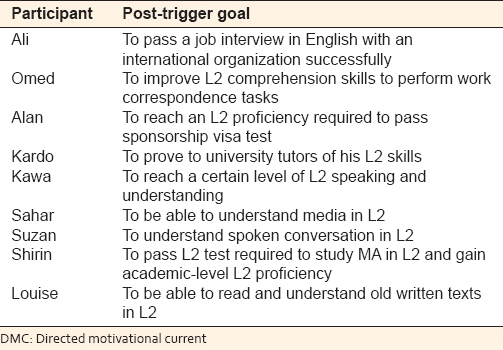

However, when the participants encountered a triggering stimulus, their goals changed from general to specific, from non-L2 to L2-related, and from abstract to tangible [Table 3]. This shift seemed to be necessary so that they could direct their energy toward a clearly defined endpoint. Furthermore, having a specific goal helped some of the participants to form a sensory reconstruction of their goals, i.e., changing a goal into vision.

Table 3: Participants’ DMC goals

3.3.2. Perceived control/feasibility

The second condition that was identified in the analysis was the perception that one had the capacity to participate in and complete all the activities leading to the accomplishment of the DMC goal, and that the challenge posed by the goal was reasonably compatible with one’s perceived abilities. This condition was pinpointed when a few participants discussed their pre-DMC disbelief they held about the goal feasibility. Shirin, for example, had previously wanted and made attempts to improve her English skills, but had not been successful, mainly because she had the perception that her home country was not an appropriate environment for learning:

In fact, I for long wanted to improve my language skills, but was unable to do so… Previously, even though I wanted to learn English, I didn’t know how or didn’t believe that making an effort on my own would be useful. (Shirin, Q 2)

Therefore, a main objective behind applying for a government scholarship to study abroad was to find the mechanism through which she could improve her English skills: “When I applied to this scholarship, it was very important to me to go to an English-speaking country especially the UK….” (Shirin, Q 3)

In addition to ensuring that one believed in one’s own abilities to engage in and successfully overcome the challenges of the goal, the analysis also identified the need for the perception that the tasks leading to goal attainment were reasonably accomplishable. For example, although he previously felt the significance of learning English, Kawa was avoiding it mainly due to his perceived fears in the language. However, once he realized English was not “too difficult” or “that complicated,” his 2 years old DMC started and a random event leading to this realization functioned as a triggering stimulus:

… So, what happened was I came across some written material in English, a story, and once I read a bit of it, I realised it was not too difficult to me or that complicated. I felt I was not too bad at it…. (Kawa, Q 1)

In both of the cases mentioned above, the lack of confidence in one’s own abilities and perception of goal/task feasibility were overcome only when a strong triggering stimulus became available. As such, the pre-existing fear and reluctance immediately disappeared as the triggers functioned to alter the perception of inability.

Despite that a sense of control was only acquired after a DMC trigger, the data suggested that the pre-DMC fear and sense of inability were largely perceived- and not real. Although Shirin had previously held the belief of inappropriateness of her home country environment, she indeed started her intense learning while still in Kurdistan- that is, before making the trip to the UK. Similarly, the story that changed Kawa’s perception and triggered his DMC was written in a simple enough language for him to understand; this indicates that he was previously unfamiliar with the degrees of the L2 difficulty to make an informed assessment of both his ability and the challenge of the L2.

It is important to mention that none of the participants, including those who suddenly acquired a sense of control/feasibility, perceived the DMC goal/tasks to be too easy, but reasonably challenging. For example, when Alan was advised of the new German proficiency requirement, he found it “shocking” and even “sad news,” and as a native and resident of Iraqi Kurdistan, he was not initially ready for this and had second thoughts about taking a preparatory course in Syria. However, when he gained the confidence that achieving the required L2 score was “difficult but feasible,” he decided to stay in Syria and thus his intense experience started, although he still had doubts if he was up to the challenge:

At the beginning, I found it difficult and challenging. However, for any goal, if you know the duration and when it ends, it would be easier and you try harder for it… When we first started, it was very difficult because the language was entirely new to me. But the teachers’ method of explaining was rather comforting. (Alan, Q 1)

A closer look at this excerpt reveals that even when Alan was enrolled in the course, he still did not see a balance between his capacities and the new language. Yet, the perception that the duration required to study German and pass a proficiency test is only a few months and the comfort provided by his teacher’s method created a sense of feasibility.

4. DISCUSSION

The main question of this study was what might lead individuals to experience periods of intense motivational engagement, a newly-conceptualized phenomenon called DMCs. The potential for this unique experience is highly appealing to increase motivation especially for L2 learning which is characterized by a constant cycle of fluctuations. Once in a DMC, people exert the optimal level of effort for an extended period of time. Language learners particularly can benefit from this experience to learn and improve their L2 skills substantially.

All the DMC cases studied and presented in this study had clear starting points standing out as the beginning of a different motivational experience. This may partially validate the occurrence of an intense and sustainable motivational experience as an independent and valid psychological phenomenon. All the participants associated the birth of their DMCs with certain personal circumstances and even more so with a specific event supporting the notion that a “DMC never simply drifts into being but rather is triggered by something specific” (Dörnyei et al., 2014. p. 14). The data contained examples of inducing triggers, such as receiving new information and opportunities, negative emotions resulting from unpleasant situations or events leading to a sense of awakening, or meeting friends sharing an L2 learning goal. Nevertheless, the findings suggested that the power of a trigger remains dependent on a set of pre-existing conditions which, although not sufficient to give rise to a DMC, pave the ground for a potential trigger to be effective. These conditions were having a general goal or personal aspirations, the perception of goal feasibility and one’s own control over the tasks needed to reach that goal. Despite that Dörnyei et al.’s (2016) book on DMCs, to which the data from this study have contributed, list an additional requirement, “openness to the DMC experience” in terms of a number of personality trait conditions, the current findings did not support this hypothesis. This, in turn, can be positive for DMC-generating programmes as the exclusion of these personality trait conditions means that almost any learner can experience a DMC, regardless of inherent personality attributes.

The findings suggested that once a powerful trigger comes into effect, there occurs an almost dramatic unison between the availability of the right trigger and the fulfillment of all the DMC conditions. It was apparent that in most of the cases, the individuals had a general goal for a relatively long period before their DMCs started; however, simply having a goal did not lead any of them to experience a DMC or a DMC-like motivational surge. Furthermore, when the participants encountered with a triggering stimulus, their goal changed from general to specific, from non-L2 to L2-related, and from abstract to a clearly-defined one. This implies that whereas merely being conscious of the value and necessity of a goal does not lead to the emergence of a DMC, an inducing trigger plays a central role in maturing a general aspiration into a linguistically-specified endpoint. The underlying mechanism behind this necessary change seems to be through providing an individual with the ability to reconstruct their goal and turn it into a vision (Dörnyei and Kubanyiova, 2014) so that an individual could direct his/her energy toward a clearly-envisaged endpoint.

On the other hand, in order for an individual to experience a DMC, s/he needs to hold the belief that s/he has the capacity to participate in and complete all the activities leading to the goal accomplishment. Acquiring the perception of a challenge-skill balance was found to be necessary, as an imbalance leads to the appraisal of the goal as either too easy or too challenging; whereas the former leads to boredom and loss of interest, the latter obstructs a sense of perceived control and progress (Csikszentmihalyi, 1988). Maintaining this balance has also been proven to have a positive effect on the quality of experience (Moneta and Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

5. CAN DMCS BE INDUCED?

The notion that DMCs are unique experiences, and as we saw that their emergence requires unique combinations of a variety of factors might not sound as good news for educators who aspire to implement DMCs in their L2 learners. Nevertheless, this research can provide us with important insight on how we might discover the individual factors that led to these DMC cases and then combine them together for optimal potential results. As the data suggested, the moment when a person is ready to proceed into a DMC is determined by a host of contextual factors; however, the presence of these factors might not necessarily lead to the emergence of a DMC. For example, creating and setting a goal (Locke and Latham, 2005) in an L2 learner might be useful, but not always effective or a sufficient element. Most of the participants of this study had had the goal of improving their L2 skills for a long time without making a strenuous effort to achieve this goal.

The challenge in the notion of inducing a DMC might as well be in the fact that a DMC is mostly a matter of personal contingency, and therefore, knowledge on one’s internal values, goals and ambitions as well as fears and frustrations might be necessary to possibly predict the effectiveness of any single stimulant. Some participants had a history with attempts to improve their L2 but were not successful because of how they perceived their likelihood of success, their actual belief of the real necessity of the L2 acquisition, or a lack of right external incentives and circumstances. Therefore, it seems that individual treatments are required for individual learners taking their personalities and internal, and the entire psychological process into account.

With these limitations in mind, I believe that there is still room for work around how we might generate a motivational current, and this very research has informed us just that. In the end, we may never be able to control the entire personal and psychological processes one is going through at any given time; therefore, we might be better off, at least at the initial stages, aiming for generating not only what we have called the DMC trigger but also moments of realization. One such a technique might be selecting verbal provocations, such as a strong single statement that might not only awaken an individual of the value and significance of L2 learning but also and perhaps more importantly, ignite a deep process of self-talk in which one reflects on what could happen if they maintain his/her status of inaction. This is in line with the latest theorization of motivation in the form of the L2 self system (Dörnyei, 2009) which, based in part on the Markus and Nurius (1986) concept of possible selves, assumes that individuals might be motivated toward action once they perceive a negative self-image in the future. As these negative emotions arouse a deep, and mostly overwhelming sense of urgency to reduce discrepancies between one’s current and desired future selves, a DMC experience maintains its strength in large part through a constant sense of improvement, transformation and progress not only in one’s L2 skills but also in one’s entire identity, self-image and personal growth (Ibrahim, 2016a; Waterman, 1993).

6. CONCLUSION

DMCs are periods of exceptional motivational intensity in goal-directed behavior. Once applied in second language learning contexts, a DMC enables learners to function at an optimal level of engagement and productivity. As DMCs are not thought to be everyday experiences, unique personal and contextual factors, play a role in inducing them. Understanding these factors is crucial for L2 teachers, so they prepare the ground for any DMC-generating programmes. This qualitative study is an attempt to investigate these factors and the overall initial conditions preceding the birth of a number of DMC cases.

The results provide significant insight into the conditions and specific triggers contributing to a DMC birth. Importantly, in almost all the cases, one particular experience of frustration, awakening, realization, or perceiving an opportunity through new information or meeting others with the same passion led to the launch of the participants’ DMCs. The findings also point to the importance of the ability of an individual to link L2 learning goals to a broader vision of personal growth and development for which learning or improving an L2 is necessary. Yet, once in a DMC, the goal needs to be specific, linguistically defined and viewed as feasible. As such and on a practical level, teachers might need to do more than indicating the importance of learning and improving the L2 as acknowledging this fact remains insufficient to trigger a long-term motivational burst; learners need to envision a better life, and themselves as more proficient individuals in the future for which learning the L2 is perceived as determining.