1. INTRODUCTION

Editorials, known as the voice of newspaper, are a public discourse that communicate with a mass audience and play an obvious role in the determining and shifting of public opinion (Van Dijk, 1996). As editorials convey the official position of a newspaper on a socially crucial and current topic, they are supposed to contain a significant persuasive value (Sheldon, 2009). Hence, to be able to effectively express their ideas, editors should take extreme care in the use of their strategies in convincing the audiences. Although the editorial is an explicit case of persuasive writing and it sets standards for written persuasion for a specific purpose (Ansary and Babai, 2005), expecting the audience to accept the presented ideas very easily is not rational. Hence, a careful description of the editorial’s structure, style, and use of lexicogrammatical features such as interactional metadiscourse markers play an essential role in achieving the communicative purpose of this persuasive genre. According to Williams (1981), argumentative texts like editorials by the use of interactional metadiscourse markers strengthen the relationship between the writer and the reader. Among the interactional metadiscourse markers (i.e., hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions and engagement markers), hedges and boosters are essential features for writers to clarify their epistemic stance and position related to the writer–reader interaction. Hedges mark the unwillingness of the writer to present propositional information unconditionally and certainly (Hyland, 2004). Through presenting information as an opinion rather than a fact, they emphasize the subjectivity of a position and therefore open that position to negotiation. On the other hand, boosters are considered as features that express the writer’s strong confidence for a claim (Holmes, 1982) and assurance and affirmation of a proposition confidently (Abdi et al., 2010).

The conventions and patterns of the genre and the writers are writing in and affect different aspects of interaction. Therefore, comparing the style and structure of editorials and their use of hedges and boosters written by English and non-English writers from different cultures brings about useful understandings of the differences in their rhetorical patterning and persuading strategies.

Despite the wide-ranging discourses that have been under study, editorials who attract a very wide readership have not been given enough attention in terms of using hedges and boosters in their rhetorical structure. Studies at the microlevel have been limited to research such as those by Le (2004) who investigated some interactional markers such as evidentials, person markers, and relational markers in newspaper editorials and by Khabbazi-Oskouei (2012), Kuhi and Mojood (2014), and Fu and Hyland (2014) who did an investigation of all interactional metadiscourse markers in magazine, newspaper editorials, and opinion texts, respectively. All these studies found that, in English editorials and opinion texts, the frequency of the use of hedges is higher than boosters. Although Fu and Hyland (2014) conducted a qualitative analysis, the classification done for hedges is limited to verbs, adverbs, and modals. Moreover, it has not prepared a clear classification for categories of boosters, and again, it seems to be a neglected persuasive strategy. Hence, it raises the need for a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis of both hedges and boosters deeply.

So far, only Tahririan and Shahzamani (2009) and Trajkova (2011) have investigated specifically the use of hedges in the editorials but not in connection with the macrolevel study or in their rhetorical moves and steps. In the former study, they used Varttala’s (2001) framework that considered all hedges as a subcategory of modal auxiliaries and the framework is not very comprehensive; hence, the findings are not in depth. On the other hand, Trajkova (2011) compared the use of hedges in only 9 English (American) and 9 Macedonian editorials which are not an enough data to generalize the findings. The findings revealed the use of more hedges in the American editorials than the Macedonian ones. Moreover, his framework was only including modal lexical verbs and modal epistemic verbs. In addition, he has considered must, will, can, and ought to as a hedge while they are showing tentativeness of the writer.

Another comparative study by Tafaroji et al. (2015) revealed the use of more boosters than hedges in both American and Persian newspaper articles. Reviewing the literature reveals that boosters have been completely neglected, so it inspires more investigation on the use of hedges and boosters in different rhetorical moves and steps of editorials. Finally, a comparative study of the structure of newspaper from two different cultures is scarce. The current study thus aims to fill the gap in research and compare American and Malaysian editorials in terms of their style and conventions of hedging and boosting statements which have not been investigated before.

2. DATA ANALYSIS AND METHODOLOGY

2.1. Data

To achieve the objectives of this study, the required data in the form of newspaper editorials that is 120 from each of the New York Times (NYT) and New Straits Times (NST) were selected. To avoid personal biases and the researcher’s influence on the data selection, an online number generator was used to randomly select the data from the websites of the NYT (i.e., www.nytimes.com) and NST (i.e., www.nst.com.my). To have a better insight of the NYT and NST, the background of each newspaper is provided in the next section.

The first step of the analysis was to read the 240 editorials from both the NYT and NST for move identification and step labeling. The second step was exploring the use of hedges and boosters in different rhetorical moves and steps which was done manually because it allows a more in-depth analysis of texts (Hyland, 1998). Moreover, as the analysis was function-based and making a distinction between propositional and non-propositional meanings of the text needed the context, manual analysis was more efficient.

2.2. Background of the Newspapers

The NYT is one of the largest American daily newspapers, which covers general news about various issues in society not a specific one such as economy or business. The NYT avoids sensationalism and follows a restrained and impartial style in reporting the news. The newspaper believes in objective presentation of news and attempts to maintain ethics of journalistic writing (The New York Times Company, 2008). It is also a popular newspaper among the authorities within the USA and around the globe. Therefore, the propositions put forth in the editorials could have significant consequences in society by making the authorities think critically of the issue raised.

NST is a mainstream, influential, and authoritative English newspaper published in Malaysia. NST not only addresses issues pertaining to the government and corporate sectors but it is also the choice of intellectuals, young professionals, and students and maybe the future leaders of united modern Malaysia (NSTP, 2013). The NST is known as a right-wing newspaper that has close ties with the government and favors their policies (Pang, 2006). According to Malaysia Annual Report, there is a regular check of the racially sensitive issues by the government and pressure on media which usually leads them to self-censor or withhold from voicing controversial issues (Reporters without Borders, 2007).

2.3. Analytical Framework

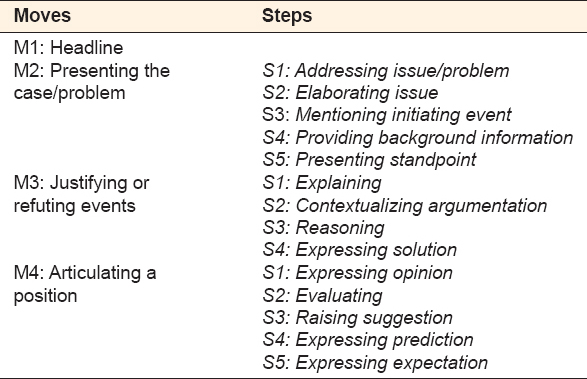

As the study is conducted at both macro- and micro-levels, for the macro level (generic structure), Zarza and Tan’s (2016) framework is deployed as it is more detailed, comprehensive, and robust (including both moves and steps) in comparison to those available in the literature (Bhatia, 1993; Ansary and Babaii, 2005). As shown in Table 1, the generic structure of editorials involves four obligatory moves’ headline, presenting the case, justifying or refuting the events, and articulating the position that is used to persuade the readers. At the lower level, these moves include 15 steps to pave the way for each move to easily achieve their communicative purpose which is persuasion.

Table 1: Framework of moves and steps in editorials

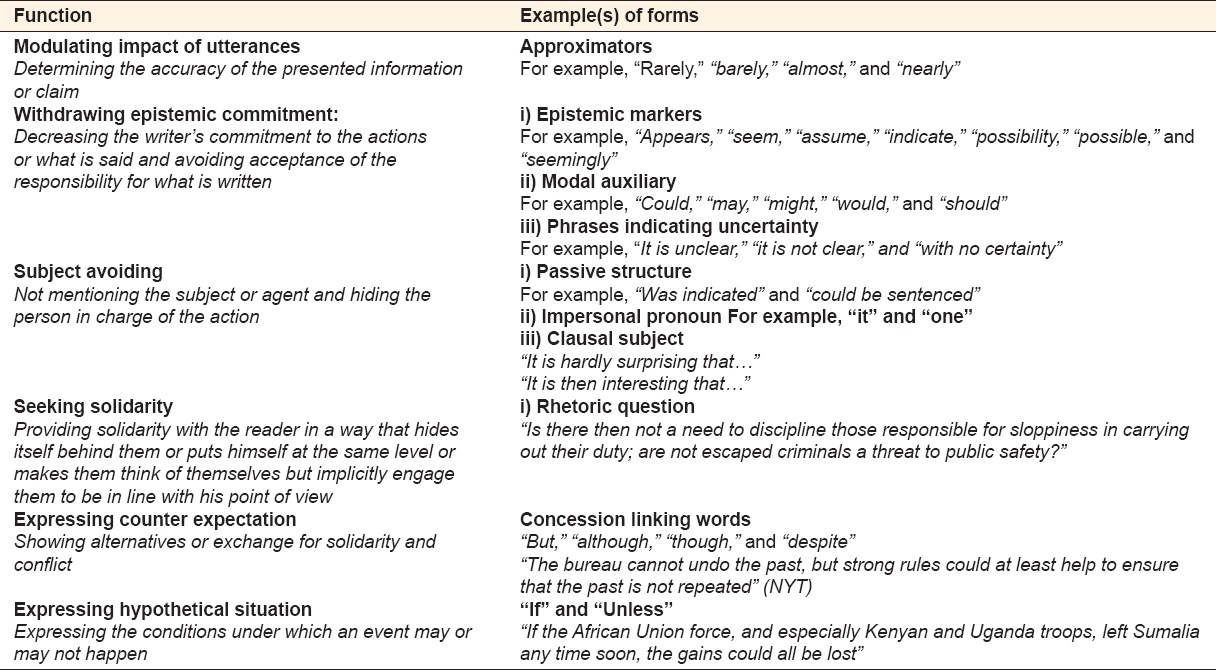

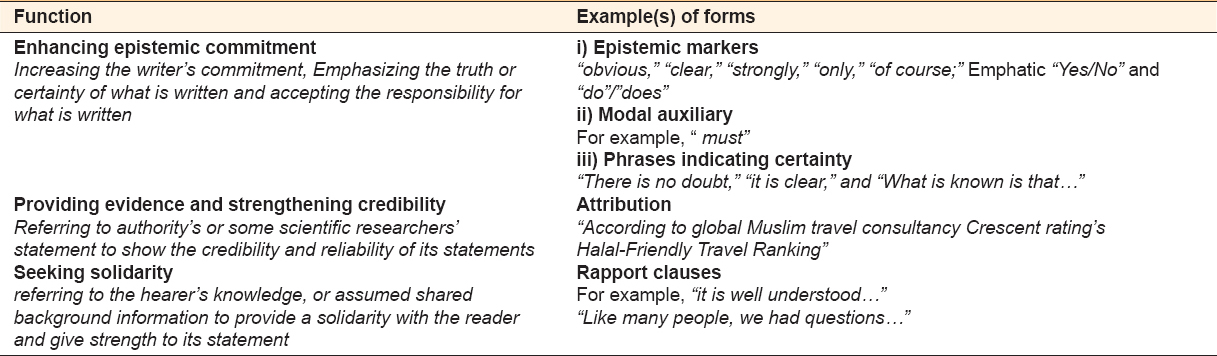

In addition, for the analysis of the data at the microlevel, the researcher conducted a pilot study on 60 editorials of NYT and NST, checked the available frameworks in the literature (Dahl, 2004; Vande Kopple, 1985; Crismore et al. 1993; Hyland, 2005), and prepared an adapted framework to the data of the current study (Krippendorff, 2004). Exploring all the previous studies revealed that although Hyland’s (2005) model is a more theoretically robust one, none of them are providing a detailed categorization of different functions of hedges and boosters specifically. Therefore, to achieve the objectives of this study, a more comprehensive analytical framework on hedges and boosters through refining, revising, and adjusting the existing frameworks was prepared. As a result of the pilot study, a theory-driven and data-driven framework for analysis of the whole data was drawn up [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2: Framework of analyzing hedges in editorials

Table 3: Framework of analyzing boosters in editorials

Finally, to elevate the reliability of the coding process, 20% of the data was analyzed independently by a PhD holder of the English language specialized in discourse analysis. Wherever there were any discrepancies between the findings of the coders, a consensus on the coding and categorizations was reached. Moreover, a three-session interview with an ex editor of the NST increased the reliability of the findings and improved the codes and categories.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section will represent findings related to the use of hedges and boosters mapped onto different rhetorical moves and steps and their rhetorical and persuasive functions.

3.1. The Use of Hedges and Boosters in NYT and NST Editorials

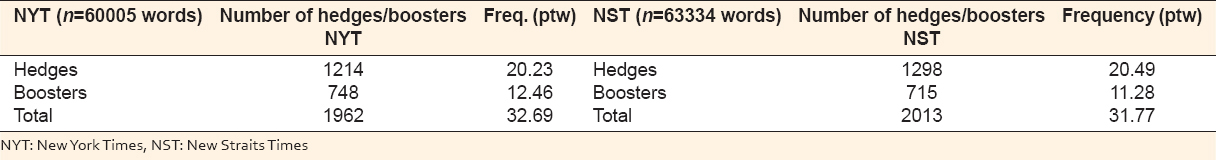

The exploration of the data revealed that there is a common pattern in both the NYT and NST as they similarly use more hedges (NYT = 20.23 and NST = 20.49) than boosters (NYT = 12.46 and NST = 11.28) in their editorials [Table 4]. However, it was also found that the use of hedges in the NYT editorials (i.e., 20.23 per thousand word [ptw]) was more frequent than their Malaysian counterpart that had a frequency of 20.49 ptw. On the other hand, boosters occurred more frequently in the NYT (12.46 ptw) than in the NST (11.28 ptw). This finding is in line with that of Kuhi and Mojood (2014), Khabbazi-Oskouei (2011), and Fu and Hyland’s (2014) study that found hedges more frequent than boosters. Using more hedges possibly be attributed to the convention of the English editorial genre to be more tentative in expressing their ideas and not to express their authority explicitly (Kuhi and Mojood, 2014).

Table 4: The overall frequency of the use of hedges and boosters in the NYT and NST editorials

3.2. Hedges and Boosters Mapped Onto Move Structure

The findings of the study revealed that, in the NYT and NST editorials, there were some similarities and differences in the occurrence of hedges and boosters in their various moves. This section will comment on the use of these persuasive strategies with significant frequencies in each rhetorical move and its related steps.

3.3. Move 1: Headline

Headline, the first move in both the NYT and NST editorials, provides the readers with the main idea of the text as it juxtaposes the most essential points of the issue in summary. The findings revealed that this move did not include hedges and boosters. Headlines in editorial genre have a tendency to use content words, such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives while using function words such as personal pronouns and articles and particularly metadiscourse markers (hedges and boosters) is not a convention, and they are rarely found (Saxena, 2006).

-

Transforming politics (NST, October 12, 2013)

-

Haiti’s Long Road (NYT, January 1, 2013)

3.4. Move 2: Presenting the case

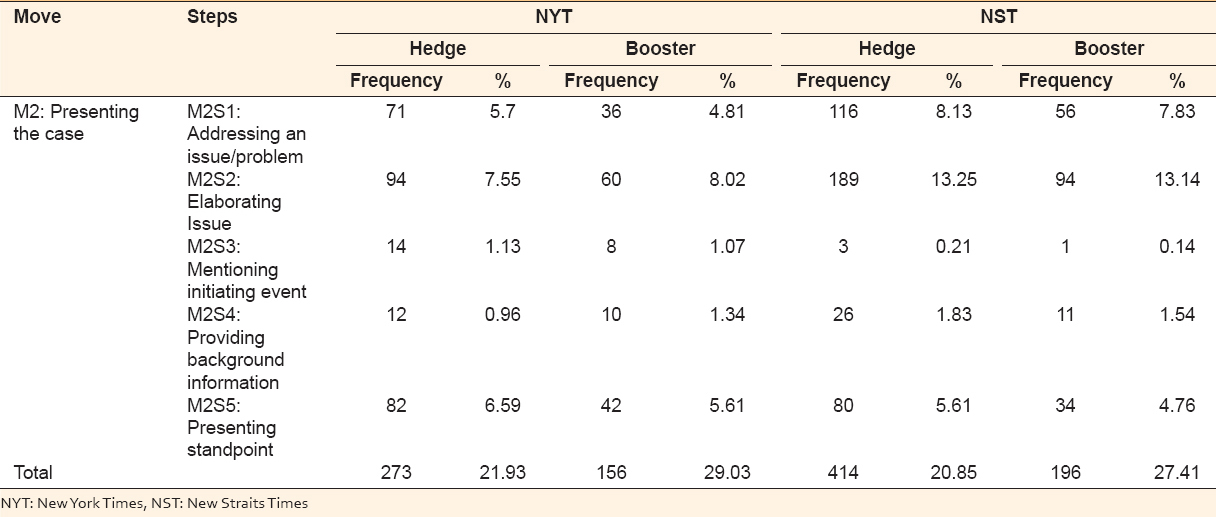

In Move 2, the editor presents the issue that the newspaper is interested in and argues its position by elaboration on the issue through facts and background information either directly or through the historical or the social context. The comparison of the two newspapers displayed a possible tendency of various moves to follow a common distribution pattern of hedges and boosters. In both the NYT and NST, the last ranking of the use of hedges (NYT = 21.93% and NST = 29.03%) and boosters (NYT = 20.85% and NST = 27.41%) belonged to Move 2. It could be attributed to the communicative purpose of this move that prepares readers with information about the addressed issue in the editorial. Therefore, the editor rarely attempts to persuade the reader in this move as much as the other rhetorical moves, which caused its less use of persuasive strategies such as hedges and boosters.

The rhetoric aim of Move 2 accomplishes by the use of various steps, and the distribution of hedges and booster in each of them based on their function is diverse [Table 5]. According to Hopkins and Dudley-Evans (1988), these diversities in purpose can affect the degree of using rhetorical strategies (i.e., hedges and boosters in this study) by various steps of the related move for engagement, expressing attitudes, and so on.

Table 5: Frequency of hedges and boosters in the rhetorical steps of M2

As demonstrated in Table 5, among the various steps of Move 2, elaborating issue in both the NYT and NST editorials includes the highest number of hedges (NYT = 7.55% and NST = 13.25%) and boosters (NYT = 8.02% and NST = 13.14%). The editor in this step provides more detailed information and enriches the editorial helping the newspaper as an informed and well-placed authority to persuade its readers. Therefore, it attempts to use hedges and boosters in this essential step to find that such information is credible and reliable. Furthermore, the use of figures and numerical information in this step makes the writer use approximators to save the face of the writer and readers.

(3) Some 650,000 Syrians are now registered as refugees by the United Nations or awaiting registration, an increase of almost 100,000 in the past month alone. That includes about 155,000 in Turkey, 148,000 in Lebanon, 142,000 in Jordan, 73,000 in Iraq, and 14,000 in Egypt. Thousands more are not registered. The total could reach one million this year. Many Syrians have fled because of bombings by army troops, still others because of sexual violence. According to the International Rescue Committee, refugees identified rape - including gang rapes in front of family members - as a “primary reason” for fleeing (M2S2) (NYT, January 20, 2013)

In excerpt 3, the NYT editor attempts to familiarize the reader with the issue completely based on statistics to show the negative effects of the dictatorial rule of Bashar al-Assad and the depth of this disaster. However, the use of statistics is modulated through the use of hedges to introduce fuzziness into the propositional content by displaying a lower accuracy of the expressed proposition (Jalilifar and Alavinia 2012).

(4) In the last three weeks, in Penang alone, five shooting incidents occurred, several of them fatal. In April, a senior Customs official was shot dead on his way to work. The case is yet to be solved. More recently, the head of an anti-crime watchdog group was shot in Seremban. He is fighting for his life. The latest incident involved the first chief executive officer of AmBank, who was gunned down in Kuala Lumpur in broad daylight, killing him and injuring his wife (M2S2) (NST, July 31, 2013).

In excerpt 4, after familiarizing the reader with the main issue of the article that is the lack of safety in Kuala Lumpur, the NST editor attempts to offer some real examples of the occurred violence. It is to prove that violence is increasing in Malaysia and leads the reader’s attention to the misery that was never a concern before. However, it uses the passive structure as a hedging strategy to not mention the agent of these issues in the society and to save the face of the people in charge.

The next step for using hedges and boosters in Move 2 belongs to presenting standpoint (hedge = 6.59% and booster = 5.61%) in the NYT. This step presents the writer’s claim and point of view with respect to the presented issue from the beginning. Being an article that is not signed by the writer (Bolivar, 1994), the editor has a tendency to support the editorial article regarding the addressed issue by presenting his/her standpoint. The editor, as illustrated in excerpt 5, presents his/her position tentatively in the format of if conditional clause. It assists the editor to decrease the level of his/her commitment and criticism on the political parties.

(5) The Election Commission (EC) promises the country a “best ever” general election (GE). Set for May 5, 2013, with April 20 nomination day, this will offer candidates the longest campaign period in recent elections. Pitting themselves one against the other, over this period, the two coalition fronts must, therefore, restrain their workers and supporters and urge them to play by the rules. [As the EC chairman makes clear there is nothing the EC can do if political parties are bent on creating chaos] (M2S5). (NST, April 12, 2013)

In excerpt 6, the editor in addition to addressing the issue of Afghanistan (M2S1) shows the newspaper’s position (M2S5) that the issue is a natural thing by mentioning it “should come as no surprise.” Editors typically plan to involve both supporters and opponents in the agreement with their position using strategies that employ a degree of conventional intimacy. One way of creating this sense of solidarity is using boosters to appeal to the reader as an intelligent coplayer in a close-knit group (Hyland, 1998). Using this phrase, the writer shows the certainty through bringing about a solidarity between writer and readers in having the same idea about the lavish spending of the Central Intelligence Agency.

(6) [The news that the Central Intelligence Agency has been spending lavishly in Afghanistan should come as no surprise](M2S1).The agency went to work in the country right after Sept. 11, 2001, and has played a dominant covert role hunting down Al Qaeda and the Taliban ever since, while the Pentagon and other agencies have pursued more transparent military and development operations costing many billions of dollars. (NYT, April 30, 2013)

In contrast, in the NST, the second position belongs to addressing issue (hedge = 8.13% and booster = 7.83%). This step indicates that there is an issue in society that needs to be addressed and discussed in detail to empower the authorities to deal with the issue.

(7) The widespread notion that the economy would pick up in the second half of 2013 was always overly optimistic (M2S1). (NYT, September 6, 2013)

In excerpt 7, “always” is an epistemic marker that plays the role of boosters and persuades readers through emphasizing the force of propositions and displaying commitment to the statement.

(8) Contextually written of thirsty sailors lost at sea, the words would become relevant if the forecasted Selangor water woes come to pass in a few years’ time. As it is, many Selangor residents have been hit by water shortages. (M2S1) (NST, February 2, 2013)

Excerpt 8 explicitly informs the reader about the problem of water shortage in Selangor which should be considered as a crucial problem with serious social consequences. The editor deploys if conditional sentence to state the information about the issue of water with cautious and tentativeness. Using this strategy has provided a condition to save the editor’s face if the water woes do not pass in the expected time.

On the other hand, mentioning initiating event was ranked as the last step that uses hedges (0.21%) and boosters (0.14%) in the NST which is an insignificant frequency. The same ranking in the NYT belongs to the providing background information in the use of hedges (0.96%).

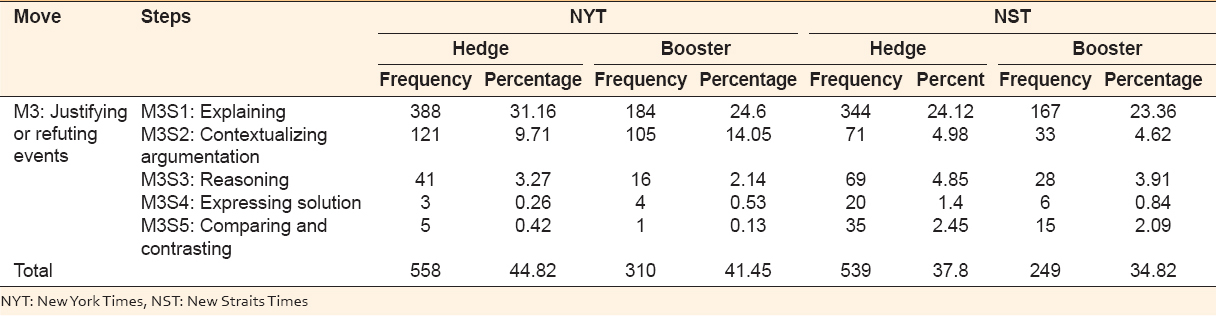

3.5. Move 3: Justifying or refuting events

This move argues the issue from different aspects with respect to the claim presented in Move 2 to justify or refute the event or standpoint. Overall, this move paves the way for the writer to convince the readers about their credibility. To achieve this aim, the writer provides satisfactory response to the questions and doubts of the reader. It is done through the use of hedges and boosters. As illustrated in Table 6, in both the NYT (44.82%) and NST (37.8%), Move 3 “justifying or refuting events” was the most frequently hedged move among the others. This high frequency of hedges in Move 3 was possibly due to the frequent occurrence of hedges (NYT = 31.16%, NST = 24.12%) and boosters (NYT = 24.6%, NST = 23.36%) in M3S1 [Table 6].

Table 6: Frequency of hedges and boosters in the rhetorical steps of M3

Explaining involves the argument of the newspaper about different aspects of the issue and discussing its pros and cons, as well as its related actions that need to be expressed persuasively. Therefore, its nature could be considered as a reason for using a high number of hedges to convince the readers to believe that its discussion and explanation are reliable and credible.

(9) On the one hand, it could be argued that if foreign workers earned as much as locals but had to spend as much, too, this might deter them from coming to Malaysia to seek employment. But this is a very naïve assumption that does not take into account that many who come to this country come from countries that offer few economic choices. But though the extras that foreign workers enjoy seemingly put locals at a disadvantage, the goal, from a macro point of view, is to make it more expensive for employers to hire foreign workers, and the increasing levy is supposed to act as a deterrent from keeping a foreigner for too long (M3S1). (NST, January 22, 2013)

In excerpt 9, the editor uses epistemic modal auxiliary “might” and “could” to express his/her uncertainty toward the truth of the proposition and decrease the commitment to the actions or what is said and to avoid the acceptance of responsibility for the judgment (Coates, 1983; Hyland 1998). In addition to modal auxiliaries, epistemic markers also withdraw the commitment and qualify the truth value of the propositional content (Catenaccio et al., 2011). Using epistemic adverbs like seemingly, the editor conveys his/her uncertainty and state of knowledge and belief concerning the information. In addition, the editor in example 9 avoids taking responsibility for what he/she claims and attempts to be objective (Buitkienė, 2008). Hiding agency in relation to the object of criticism (Blas-Arroyo, 2003) is what happens when one wants to exercise a degree of mitigation. As depicted in excerpt 9, this is possible by the use of passive structure and not mentioning exact information to save the face of the readers and the government members as the criticism maybe pointed at them.

(10) It is not clear yet whether Detroit’s officials will ultimately try to sell the collection. Michigan’s attorney general, Bill Schuette, has issued a strong opinion that the art can be sold only to acquire more art, not to retire public debt. But Bill Nowling, a spokesman for the city’s emergency manager overseeing the bankruptcy proceedings, said this week that although there are no specific plans to sell the art, all options “remain on the table”. (M3S1)(NYT, July 26, 2013)

As shown in excerpt 10, epistemic markers like “only” are another linguistic form of boosters that intensify a particular part of information or a specific stance regarding the issue. It is seen that editors deploy epistemic markers to emphasize the introduced speech act (Jalilifar and Alavinia, 2012). The writer by the use of this linguistic form of boosters highlights specific parts of his/her utterance to make the reader easily notice its importance. In addition, in the above excerpt, modal auxiliary “will” functions as a booster as it enhances the editor’s commitment to whatever he/she claims. Moreover, in different steps, there are expressions such as “it is not clear” that play the role of hedges as they express the writer’s uncertainty. Attribution as another form of boosters is used in the example above (M3S1: Explaining) that its function will be discussed below.

As illustrated in excerpts 11 and 12, attribution mostly occurs in M3S2 contextualizing argumentation. The editors contextualize their argumentation through facts and evidences which play a pivotal role in supporting the expressed opinions in argumentative discourse to make them plausible and seem acceptable (Hulteng, 1973). As depicted in Table 6, contextualizing argumentation has the second rank in terms of the use of hedges (NYT = 9.71, NST = 4.98) and boosters (NYT = 14.05, NST = 4.62). According to Wangerin (1993), argumentative texts that do not use evidences as a support are weaker in effecting the readers than the ones with solid evidences.

(11) The Obama administration continued to block his release to anywhere but Algeria, even after Luxembourg expressed interest in resettling him. During a 2009 hearing, [Federal District Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle told government lawyers she was “appalled” at the situation. “I don’t know why in the world the only thing that the government can see here is Algeria,” she said. “I think it’s our duty to try to do something about these people down there and not just say, O.K., go to where you came from”] (M3S2). (NYT, December 6, 2013)

(12) [Malaysia, according to Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak] (M3S2) is desirous of fostering a win-win relationship with Singapore. (NST, February 20, 2013)

On the other hand, the other steps of Move 3 do not include a significant number of hedges or boosters. For instance, the frequency of hedges and boosters in comparing and contrasting in the NYT (hedge = 0.42% and booster = 0.13%) and expressing solution in both the NYT (hedge = 0.26% and booster = 0.53%) and NST (hedge = 1.4 and booster = 0.84) was not significant. They were ranked as the least dominant steps in which hedges and boosters have been realized.

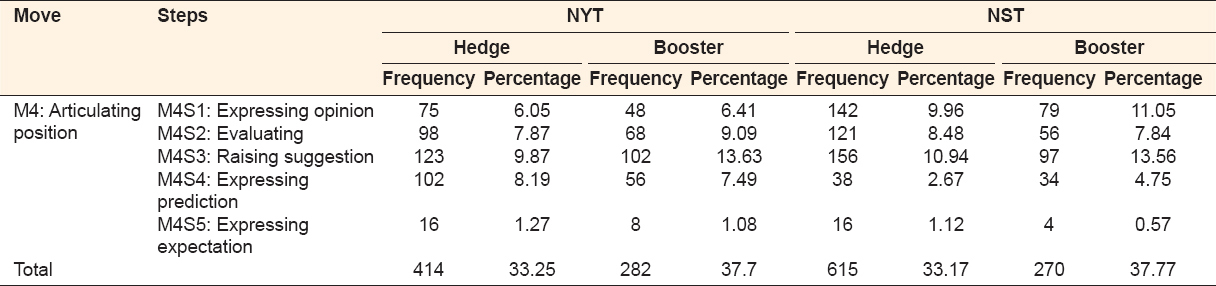

3.6. Move 4: Articulating position

This move distinguishes the editorial from other newspaper genres, such as stories, as it makes the editorial a mixture of facts and opinions or stance of the newspaper regarding the issue. However, influencing the reader using non-factual and opinion statements is more difficult than stating facts (Van Emeren et al., 2002). Therefore, it requires full commitment of the writers in articulating their position very explicitly and strongly. To this end, the editors can use specific persuasive strategies such as hedges and boosters to show their amount of commitment to their stance and position.

The examination of the data in the current study revealed that “articulating position” was ranked as the second highest move in the use of hedges (NYT = 33.25% and NST = 33.17%) [Table 7]. Moreover, the findings revealed that the NYT and NST editorials comparatively devoted approximately equal percentages of their hedges (NYT = 33.25% and NST = 33.17%) and boosters (NYT = 37.7% and NST = 37.77%) in voicing their ideas to persuade their readers. However, the NYT preferred more boosters in Move 3 justifying or refuting events to make its arguments more persuasive. In contrast, boosters in the NST were mostly occurred in Move 4 Articulating position (37.77%) in comparison with the other moves. Possibly, it implies the importance of getting agreement of the readers for the NST regarding its stance.

Table 7: Frequency of hedges and boosters in the rhetorical steps M4

Moreover, analyzing each step of Move 4, as depicted in Table 7, reveals that editors of both the NYT and NST use the most number of hedges (NYT = 9.87% and NST = 10.94%%) and boosters (NYT = 13.63% and NST = 13.56%) in M4S3 “Raising suggestion.” This indicates that hedges and boosters influence the NYT and NST’s readers to act in future regarding the issue in line with the newspaper’s position most effectively. However, in editorials, explicitly directing the readers toward performing a particular act may be more easily said than done. Therefore, both the NYT and NST editorials have a tendency to express their suggestions in a more persuasive and safe style using more hedges and boosters.

(13) If the water companies are lax then the government in Shah Alam must put its foot down instead of dilly-dallying over the re-nationalising issue and putting the spanner into the central government’s already approved plans. (NST, May 23, 2013)

(14) The homeland security secretary, Janet Napolitano, has promised a review of solitary confinement policies. If she doesn’t fix this, then Congress should step in, and now is the perfect time. (NYT, April 1, 2013)

As illustrated in excerpts 13 and 14, the NYT and NST editors have used “if” in combination with “should” and “must.” It is done to hedge their utterances and decease the force of suggestion to save the editor’s face regarding the presented recommendation.

Moreover, the NYT editorials employ a higher frequency of hedges (8.19%) and boosters (7.49%) in prediction than the NST (hedge = 2.67% and booster = 4.57%). In contrast, the NST uses more hedges (9.96%) and boosters (11.05%) in expressing opinion.

(15) It is obvious that gun violence is a public health threat (M4S1). A letter this month to Vice President Joseph Biden Jr.’s gun violence commission from more than 100 researchers in public health and related fields pointed out that mortality rates from almost every major cause of death have declined drastically over the past half century. (NYT, January 26, 2013)

(16) Analysts do not expect the convention to be broken at the next elections but believe this is something the electorate should start considering. [And, indeed, for a multicultural nation, as Indonesia is, it is certainly important for politics to be representative and inclusive] (M4S1). (NST, January 17, 2013)

In excerpts 15 and 16, the NYT and NST editors express their opinions regarding the issues by the use of epistemic adjectives and adverbs such as “obvious,” “certainly,” and “indeed” to indicate certainty about their opinion (M4S1) and remove doubts. Furthermore, they consequently increase the significance of the editor’s claims and evaluation regarding the addressed issue.

In addition, in M4S4, editors use if clause to show lack of definiteness of future prediction and newspaper’s conviction about the proposed judgment. Similarly, Bonyadi (2010) found that making prediction is realized through if conditional sentences. According to Biber et al. (2002), the logical meanings of “would” mostly express the likelihood or probability of occurrence or happening of a particular action in the future time. Based on the analysis of data, it seems that “would” has less certainty and definiteness regarding the possibility of the event in contrast to “will” (Peng, 2001). Therefore, in excerpt 17 and 18, “would” has been considered as a form of hedge and “will” as a form of booster.

(17) Mr. Suthep and his followers have concluded that there is no way the Democrat Party, which has lost every election since 1992, can win against Ms. Yingluck’s Pheu Thai Party, whose populist policies like free health care and subsidies for rice farmers has earned it the loyalty of many voters, especially those in northern and northeastern Thailand. [If they manage to depose the Ms. Yingluck’s government, the supporters of Pheu Thai will take to the streets as they did in 2010] (M4S4). (NYT, December 23, 2013)

(18) This new system, if transparent and cleansed of patronage and nepotism, has the potential of producing the best from among some three million. [If all Barisan Nasional component parties follow this lead, the final outcome is a coalition of leaders built on merit alone. Would this not result in a BN that faces the 14th General Election transformed and more prepared to serve the citizens?] (M4S4). (NST, October 12, 2013)

In excerpt 18, in addition to the use of if clause as a hedge, in the last sentence of this example, prediction has been expressed in rhetorical question form. Rhetoric questions function as a hedge because the writers establish a more dialogic interaction with the newspaper’s readers and thus gain acceptance for their argument (Khabbazi-Oskouei, 2012).

Finally, M4S5 expressing expectation in both the NYT (hedge = 1.27% and booster = 1.08%) and NST (hedge = 1.12% and booster = 0.57%) was the step in which the least number of hedges and boosters realized.

4. CONCLUSION

To sum up, newspaper editors draw on rhetorical strategies to influence the point of view and actions of their wide readership and authorities in charge of the addressed issue. This manipulation occurs by means of various lexical and linguistic features in different newspapers taken from different countries. The findings of this study revealed that the NYT and NST editorials, in line with the previous studies (Kuhi and Mojood, 2014; Khabbazi-Oskouei, 2011; Fu and Hyland, 2014), use more hedges than boosters. However, it is also found that the NYT and NST devise their own and particular style of hedging or boosting statements. In other words, the results obtained suggest the NYT editors preferred using boosters, while in the NST, using hedges was favored. This might suggest that the Malaysian editors preferred to be more indirect in their argument and to persuade their readers through observing politeness. However, for the American editors, indirectness could indicate weakness, which is not approved of in a person with authoritative power. It can be attributed to the social status of the NYT as a newspaper that is empowered by the absolute freedom that gives it the possibility to present its opinions with confidence and in an assertive style (Zarza et al., 2015).

In addition, based on the findings, it could be implied that the communicative purpose of rhetorical moves and steps influenced the frequency that hedges and boosters have employed in each of them. Overall, the NST uses more boosters in Move 4 compared to the previous moves, and considering each step of Move 4 separately, it is revealed that they include more hedges than boosters. It indicates that the NST editorials have a tentative voice in expressing their ideas about the issue. In contrast, the NYT editorials employ more boosters in each step to show their authority and certainty regarding evaluation, attitude, and opinion about the issue. Finally, it can be mentioned that mainly those steps in each move that convey the newspaper’s position, opinion, and attitude contain a higher frequency of hedges and boosters. These metadiscourse features function as a facilitator for the interaction between the writer and the reader to have a friendly relationship. Moreover, it makes the newspaper’s ideas seem more credible and acceptable to the readers with various backgrounds.

The findings of this study could be useful in determining the writing skill syllabus or units in a writing program. Swales (1999) opined that there are “pedagogical values in sensitizing students to the rhetorical effects and the rhetorical structures that tend to recur in genre-specific texts.” The findings of this study assist ESL/EFL students to write argumentative essays and persuade readers effectively (e.g., the use of rhetoric as an art of writing and use of hedges and boosters), as there are so many similarities in their lexis, structure, and linguistic features such as modality, connectives for reasoning, and involvement strategies (So, 2005). Moreover, considering the fact that “linguistic awareness can be more effectively developed with purposeful language practice and critical analysis of a genre” (So, 2005), the outcomes of the current study could equip ESP teachers and students with the essential understanding of the conventions in the editorial discourse. Thus, in light of the findings of the current study, ESP students may be able to write persuasive editorials that are properly organized, informative and persuasive to the audience.

In addition, the composite frameworks in this study show the importance of both theory and specific data and context in providing a comprehensive framework with minimum overlaps among their categories. These classifications of hedges and boosters along with the distinction of propositional and non-propositional meanings could be useful in the analysis of various genres based on their context.